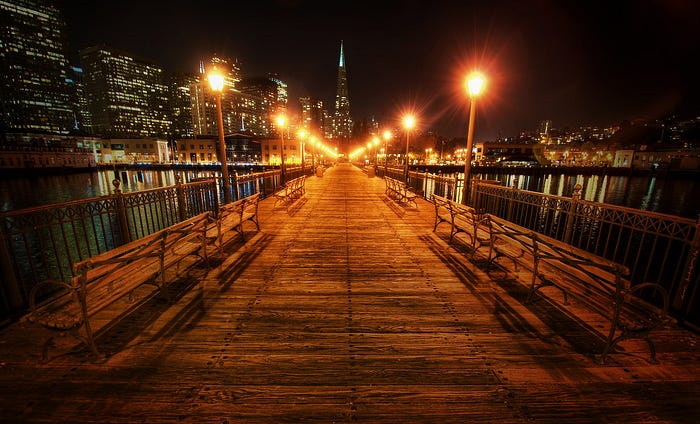

Circa: Lower Manhattan 1991

I was on a gap year from a university, trekking through the Holland a few nights a week for a part-time gig. The bar was a hole in the wall, the dirtiest of old-school dives before they became trendy. It was on the West Side, not far from the docks, and easy for me to get to by car. The money sucked, but the bar elevated me to a higher level of bartender because it was in New York. Manhattan. The City. The zip code looked good on my resume.

Even with the regular scams of cutting corners, how the door stayed open was beyond me. The speed rack had two of each rotgut liquor side by side. The right bottle was watered down, earmarked for the slumming hipsters and bridge and tunnel people with their big mouths. The left bottle was ironically called “the good stuff” and served to the decaying regulars who’d know the difference. Danny had other tricks, but they were none of my business.

I remember the night Joey walked in. It wasn’t so much Joey that caught my attention, but the brown and white marbled bulldog mix that waddled loyally inside next to him. She was short, squat, and named Daisy. She plopped down at the base of Joey’s stool and didn’t move. She could be heard snoring between song tracks playing on the jukebox while Joey nursed a free beer. He was the son of someone Danny knew, and drank for free. Usually, it was just a couple of beers, but occasionally, Danny’d give me a nod, which indicated to pour him a shot from the left.

I didn’t understand their relationship. Danny and Joey barely spoke. Hell, Joey barely spoke at all. He’d come in late, sit at the bar, hunched shoulders, staring at the bar top. Sometimes he’d nod off and jolt awake with a shudder or a head jerk. After a few hours, he’d leave with Daisy trailing behind him. This went on for a month before Danny clued me in. Joey was a heroin addict.

I never met a junkie before. My only reference was the portrayal in fictitious Hollywood cautionary tales, and I found myself infatuated. I had all kinds of questions I wanted to ask, but didn’t because we were all pretending not to notice. Instead, I’d wipe down bottles or flip through a magazine, sneaking glances at him. I’d catch glimpses of who he used to be at certain angles, illuminated by cheap tea lights — possibly a good-looking guy layered in street dirt, facial scruff, and immense self-loathing. He was a year younger than me, and I wondered where his parents were or why he wasn’t in school. My deluded middle-class ignorance wouldn’t allow me to wrap my head around his lifestyle.

Danny was an enabler. I knew it, Danny knew it, and, more importantly, Joey knew it. But feeding Joey alcohol and having him sit at the bar through various states of high or withdrawal was better than being out on the street. It was also better for Daisy. It didn’t take long for her to start showing signs of neglect. Stopping at a Bodega to buy an overpriced can of dog food on my way into work became a ritual. I’d empty the can onto a patch of cocktail napkins and put it in front of her. Half the time, Joey didn’t even notice as Daisy inhaled it. Sometimes I wondered if that was all she had to eat that day, that week. I’d scratch her head, clean the gunk from her eyes, and say kind, soft words to her.

Over the coming months, I grew keen to Joey’s varying states of existence. I picked up on the subtle notes of his highs and lows as well as the obvious telltale signs of heroin addiction. I no longer needed Danny to tell me when to give him the straight liquor or when a couple of beers would hold him over. Daisy’s visible ribcage was also a good indication of when Joey was coming off a bender.

Then one night, after months of the same routine, Joey didn’t come in. It was early fall and the end of a bizarre Indian summer. The nights were cold again. I planned on asking Joey if I could buy her a sweater. Danny advised against it, predicting Joey’d sell it for a couple of bucks. But the conversation never happened. By 3 am, the bar was desolate, and Danny called it a night. Daisy’s can of food sat near the register, already open and still waiting. He ran the tape, pulled the money out of the register, and retreated to his office. I grabbed the garbage bags and took them out back.

Joey was propped up against the brick wall next to the dumpster. His arm still tied off, needle dangling, streaks of dried blood down his forearm. In the white light cascading down on him from the security light above, I saw his face clearly. Traces of foamy spittle collected in the corner of his mouth, smeared across his chin and cheek in a thin sheen, frozen by the cold air. Death had washed away the pain and misery of being alive, of being a junkie. The lines on his face melted upon the release of his soul from his earthbound body. He was beautiful, like I had suspected he would be. I preferred this angelic display over the haggard junkie nodding at the bar. In my mind, he’d stay young forever.

When I couldn’t find Daisy, I went in for my shifts early to ask around. The day Joey died, I was told he sold Daisy to a guy down at the docks for twenty bucks to buy a couple of balloons. One of them was the hotshot that killed him.

I never saw Daisy again.